The twentieth century, or the era of extremes, were the years that presented humanity an increasingly globalized world, but that, at the same time, demonstrated the ability of the most different leaders and societies, under certain conditions, to carry out the most atrocious violence in favor of its causes. The marks of imperialism around the world, the neo-colonial oppression in constant expansion, the intense and progressive arms development of the most powerful nations on the planet, all produced a devastating result: war.

The second decade of that century came to show the world the direction our decisions were taking us, and, worse than that, under the blood of millions of men, women, and children, the seed of the most obscure movement that humanity would come to know was planted and prepared to rise in the Europe of that time, a few years after the fire ceased between the trenches.

The structures around the globe were shaken, a continent in ruins, plagued by the evils of inequality, misery, hunger, and unemployment. Under the imposition of innumerable sanctions, due to the hatred of the countries considered the losers of the war, the snake’s egg was placed, which would reveal its face to the world in the following years.

At that time, the economic and social crisis brought about by armed conflicts and the iron hands of men who dedicated themselves to unifying their nations around vile objectives began to write one of the darkest chapters in world history.

Do you know what this period is about? Do you know where fascism came from?

The years in the aftermath of the Great War were marked by a series of literally revolutionary events, especially with regard to the European continent. In this scenario, the need for solidarity among workers from all over the continent, in order to combat the strong social ills that were being established at that time, resulted in the advance of union movements in several countries, which were also greatly influenced by the recent establishment of Soviet socialism.

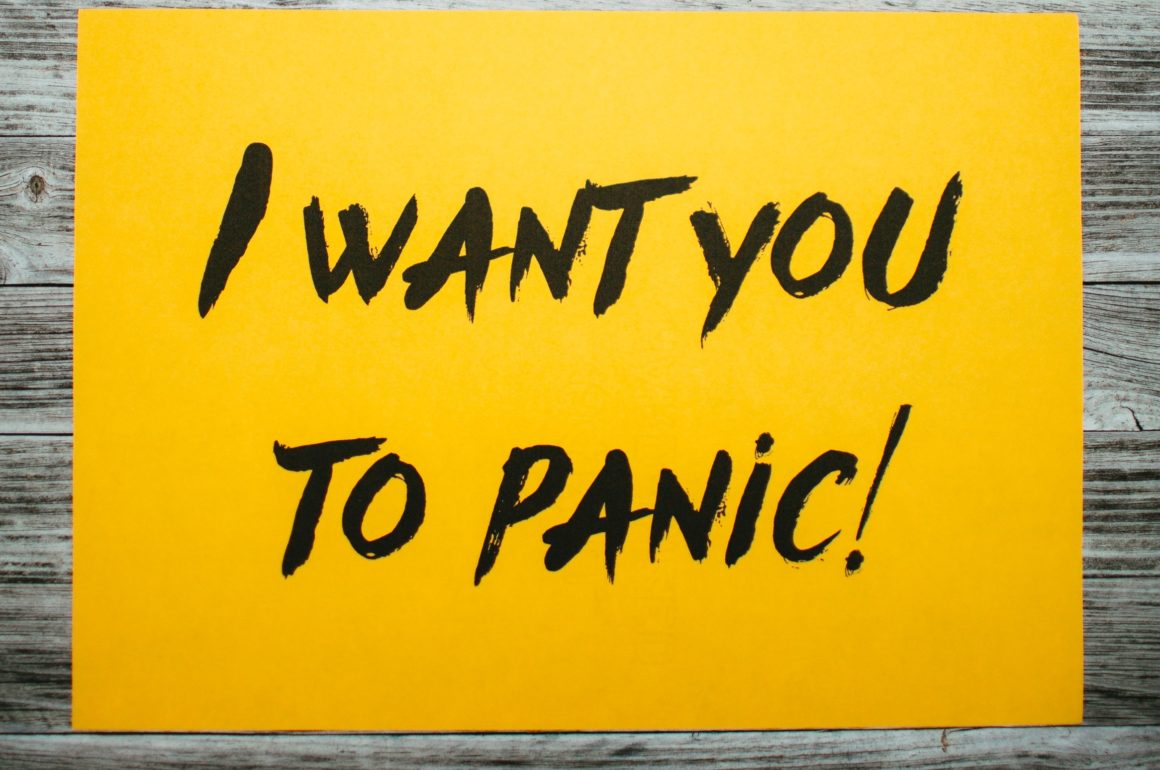

Little was known about the future, much was speculated about the years to come, but only one feeling ruled in Europe at that moment: the fear of anything that resembled what was experienced in those bloody years of armed conflicts.

Fear is a dangerous feeling. It is able to lead normally well-intentioned people to be silent in the face of atrocities or even to support them. In fact, most people were afraid of the extremism brought by the war, but others were absolutely consumed by shame and humiliation, especially in the countries that suffered the worst international sanctions after the ceasefire, and it was under these conditions that the leaders who would translate resentment into words and actions that many would like to expound, but did not have the necessary courage, came to the fore.

Benito Mussolini, a former member of the Italian Socialist Party, expelled for supporting the country’s entry into the world war, was the first great exponent of these leaders. In 1919, he started organizing his own group, alongside ex-combatants of the conflict, and founded, in 1920, the National Fascist Party, whose main goals were the fortification of national security, resumption of the greatness of the country in the global scenario, and construction of a new, strong and respectful Italian State, with its ideology symbolized by the old fascio de littorio, symbol of power of the Roman empire. At that time, the history of Europe was being written, and one could not imagine the proportions that Mussolini’s actions would take.

In its first elections, the new party was able to occupy 20 seats in the National Congress, with deputies who began to institutionally promote authoritarian and militaristic ideas within the Italian State. For many Europeans, this might seem a worrying indicator, but for a large part of the Italian population, who saw themselves as members of a weakened and disrespected society, which has come to live with the constant fear of unemployment, economic instability, and international hostility, this approach attractive and even, for many citizens, necessary. It was how the fascist party rose politically.

Through the vote, through democracy, it was able to make its anti-democratic actions and aspirations legitimate.

In 1922, a great event was held that would change the history of the post-war forever, from a time when peace, prosperity, and stability were sought in the world, to one of revanchism, authoritarianism, and attacks on democracy. This event was the March on Rome, in which men dressed in black shirts pressured King Vitor Emanuel III to appoint their leader to the post of prime minister of the country. The move was successful. At that moment, Mussolini was consecrated as the great Italian head of state.

One of his major milestones was the creation of a fascist militia, in the name of national security, which came to exercise power authoritatively and to violently repress anyone who opposed the regime. The cult of an increasingly repressive state, violent masculinity, militarism, national symbols, and fascist leaderships became central government values as well as the extermination of everything that was contrary to its strongholds, such as socialists and other perceived subversive groups.

In the following elections, the population was violently pressured to elect members of the fascist party for the main institutional positions, and the people, who helped the regime to come to power began to question it more vigorously, mainly after the murder of one of the political opposition leaders, the socialist representative Giacomo Matteotti. But it was too late for disputes, and this opening of eyes only served as a subterfuge to make the government even more undemocratic and militaristic. From then on, it would be costly and time-consuming for the monster that was democratically created to be destroyed.

There is much to be said about the fascist regime in Italy, and also about the other countries to which it has spread ideologically. From Hitler in Germany to Franco in Spain and Salazar in Portugal, fascist ideals spread in various ways throughout Europe and were the main cause of the future World War II. Among all these cases, we highlight the common characteristics that took these ideas to the top of European politics: societies under reconstruction, suffering from the evils of inequality, unemployment, and misery, with their populations living in constant fear of the near future.

It was precisely this fear that led them to distance themselves from possible democratic ideals that were constituted at that time, to support the authoritarian, exclusionary, and violent values of anti-democratic leaders.

The feeling of generalized panic paved the way to the ascension of fascism and gave it the tools to justify atrocities on behalf of a strong, unified state.

By Pedro E.